We are currently living in an interglacial period, a relatively warm period of time during an ice age, which will last several thousands of years until the next glacial period starts. The current interglacial period, which began between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago, caused the ice sheets from the last glacial period to begin to melt and disappear away, and the process is still happening. However, the melting has been accelerated since the 1850s, largely as a consequence of human activities.

These historical photographs of glaciers, when compared with photos taken at a more recent date, shows the dramatic change in the landscape and vegetaition that resulted when the glaciers retreated. The photos were taken at various locations in Alaska, including Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Kenai Fjords National Park, and the north-western Prince William Sound area of the Chugach National Forest.

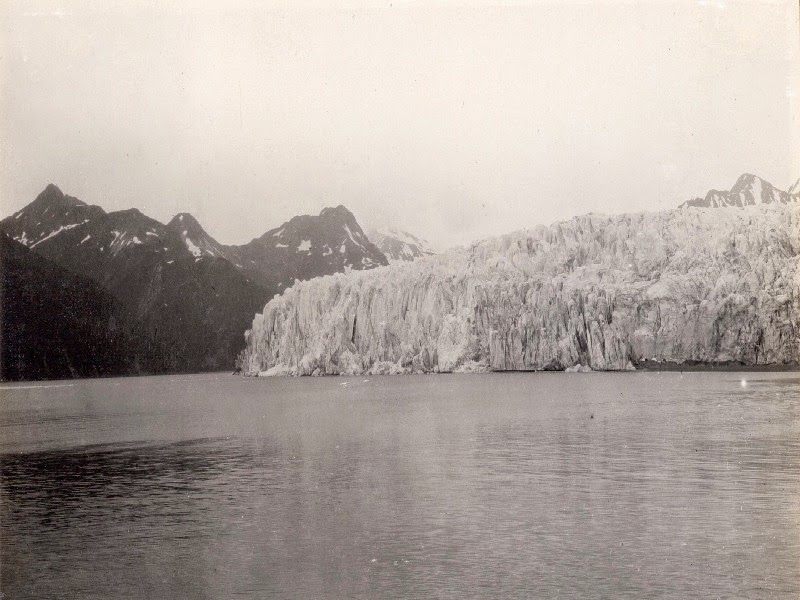

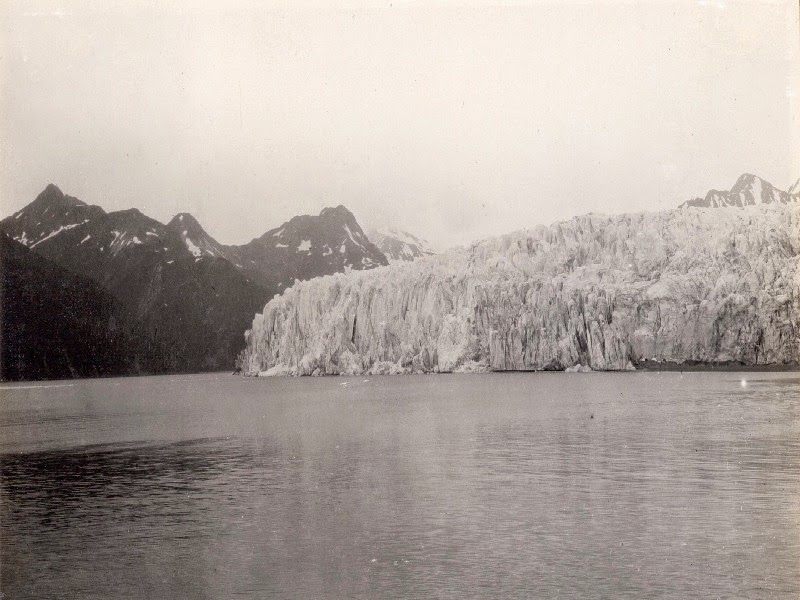

Muir Glacier and Inlet

Muir Glacier and Inlet

A photograph taken on the west shoreline of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska on September 2, 1892 shows the more than 100-meter (328-feet) high, more than 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) wide tidewater terminus of the glacier. Some icebergs, evidence of recent calving, can be seen floating in Muir Inlet.

This photograph taken from the same location on August 11, 2005. Muir Glacier is no longer visible, as it has retreated more than 50 kilometers (31 miles). During the interval between photographs, Muir Glacier ceased to have a tidewater terminus. Note the lack of floating ice and the abundant vegetation on many slopes throughout the photograph.

A photographs taken on the east shoreline of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, between 1880s – 1890s shows the more than 100-meters (328-feet) -high tidewater terminus of the glacier. Numerous icebergs, some more than 2 meters (6.6 feet) in diameter are grounded on the tidal flat in the foreground.

On this photograph taken from the same location on August 11, 2005, Muir Glacier has retreated more than 50 kilometers (31 miles) and is completely out of the field of view. The beach in the foreground is covered by a cobble and pebble lag deposit, which was winnowed from sediment that was deposited by Muir Glacier and by melting grounded icebergs.

Photograph taken on August 13, 1941, shows the lower reaches of Muir Glacier, then a large, tidewater calving valley glacier and its tributary Riggs Glacier. The ice thickness in the center of the photographs is more than 0.7 kilometers.

Photograph taken from the same location on August 31, 2004. Muir Glacier has retreated out of the field of view and is now located more than 7 kilometers (4.4 miles) to the northwest. Riggs Glacier has retreated as much as 0.6 kilometers (0.37 miles) and thinned by more than 0.25 kilometers.

Reid Glacier

A photograph of Reid Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, taken on June 10, 1899, shows the approximately 60-meter (197-foot)-high tidewater terminus of the then retreating Reid Glacier.

Photograph taken on September 6, 2003, from the same location. Reid Glacier has retreated about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) and is just visible at the head of the fiord on the left side of the field of view. The hillside in the foreground is covered with dense vegetation, including both conifers and deciduous trees.

Carroll Glacier

A photograph taken on August 1906 shows the calving terminus of Carroll Glacier sitting at the head of Queen Inlet.

This photograph taken on June 21, 2004, shows that the terminus of Carroll Glacier has changed to a stagnant, debris-covered glacier that has significantly thinned and retreated from its 1906 position. The head of Queen Inlet has been filled by sediment.

Pedersen Glacier

A photograph of Pedersen Glacier on July 23, 1909 the north side of the then retreating terminus of Pedersen Glacier, grounded on the beach above tidewater. Little, if any vegetation is present in the photograph

This photograph taken on August 13, 2004 documents the retreat of Pedersen Glacier from the field of view, a retreat of about 1.5 kilometers (0.93 miles). Diverse vegetation, featuring alder and spruce, has become established on the hill slopes and on the elevated ground of the former terminus.

Another view of the Pedersen Glacier from the mid-1920s and the early 1940s.

The second photograph dates from August 10, 2005. In the roughly 60 - 80 years between photographs, most of the lake/lagoon has filed with sediment and now supports several varieties of grasses, shrubs, and aquatic plants. Pedersen Glacier’s terminus has retreated more than 2 kilometers (1.24 miles). The tributary located high above Pedersen Glacier separated from it sometime during the third quarter of the 20th century. No icebergs are visible. Isolated patches of snow are present at a few higher elevation locations.

McCarty Glacier

A photograph taken from the mouth of McCarty Fjord, on July 30, 1909, shows the west side of the terminus of the then retreating McCarty Glacier. Little, if any vegetation is present in the photograph

This photograph was taken from the same location on August 11, 2004. It shows the retreat of McCarty Glacier from the field of view, a retreat of more than 15 kilometers (9.8 miles). Dense, diverse vegetation, featuring spruce, has become established on the hill slopes.

Northwestern Glacier

This photograph of Harris Bay, Kenai Fjords National Park, was taken between the mid-1920s and the 1940s. Shallow water adjacent to the shoreline in the foreground appears to be covered by a small thickness of sea ice, containing a number of pieces of brash ice. Northwestern Glacier spans most of the width of the photograph.

The second photograph dates from August 12, 2005. In the roughly 60 - 80 years between photographs, Northwestern Glacier has retreated out of the field of view. Sedimentation and uplift have expanded the shore area and produced a marshy wetland covered by a diverse array of vegetation.

Lamplugh Glacier

This photograph of Lamplugh Glacier was taken on August 1941. It shows the calving terminus of Lamplugh Glacier extending to within (0.8 kilometers) 0.5 miles of the photo point.

This photograph was taken on September 8, 2003. It shows that the terminus of Lamplugh Glacier has actually progressed to more than 0.5 kilometers (0.3 miles) forward of its 1941 position. Additionally, glacial sediment on the bedrock ridge in the foreground indicates that Lamplugh Glacier had advanced beyond the photo point at some time during the interval between photographs, probably in the late -1960s.

Source