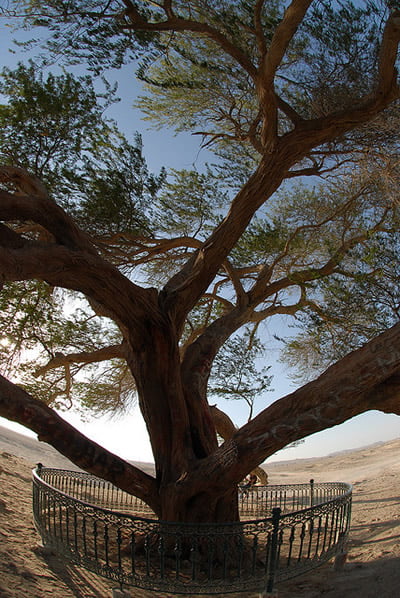

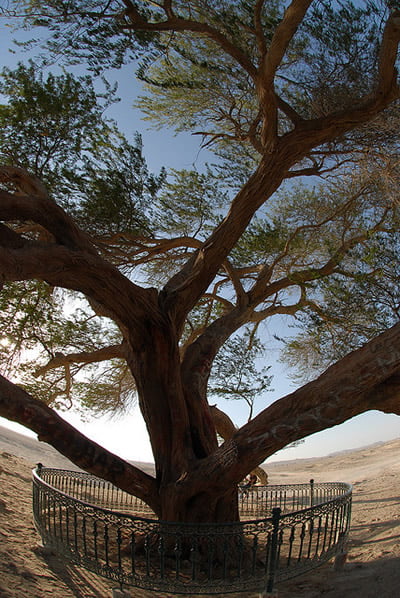

The Tree of Life or Shajarat-al-Hayat, as it is called in the local language, is a mesquite lonely tree that stands in the heart of Bahrain’s desert for over 400 years.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Faisal Ansari

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Harold Laudeus – Flickr

Both its age and its location definitely make this tree a survivor, which is considered to be a remarkable natural wonder of the world witnessed by most who visit Bahrain.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Amer Olba™ – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Faisal Ansari

It stands alone, on top of a 25-foot-high sandy hill, at the highest point in Bahrain, miles away from another natural tree and with no apparent source of water. With 32 feet in height, it has continued growing-despite the extreme temperatures, lack of fresh water, and nutrients.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Harold the Heretic – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Shady_Myskus – Flickr

It has come to be known as the Tree of life due to the very fact that the tree stands amidst a hot and dry desert with no known water source feeding, which truly represents the magic of life and the power of nature.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Harold Laudeus – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: cannopia – Flickr

Serving to increase the lure of the place, the tree’s source of water is a mystery, because it stands in a place completely free of water. Plant scientist may say that its roots go very deep and wide to get water from the reserves of sweet springs kilometers away. The local inhabitants believe with heart and soul that the tree’s longevity is granted by Enki, the mythical God of water, and that it marks the location of the Garden of Eden.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Alex Europa – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: stephenmichaelgray – Flickr

Surrounded by endless oilfields, from far away it looks like a green spot in the desert. The tree has several low hanging branches that spread out in all directions.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Glenn Rose – Flickr

Tree of Life Road – Bahrain | Photo by: triggerpit.com

The Tree of Life in Bahrain is located 1.2 miles or 2 kilometers away from Jebel Dukhan.

How to Get there:

“To reach the tree, take the Zallaq Highway heading east, which becomes the Al-Muaskar Highway. You will eventually see a sign for the Tree of Life indicating a right turn. (Although the sign seems to point you to turn onto a dirt road which actually goes nowhere, do not do so, instead wait until the next intersection which is several metres ahead). There are no signs as you travel down this road, but pay attention to a scrap metal yard on your right. Before you reach a hill which warns you of a steep 10% incline, take a right. As you continue straight down this road (including roundabouts), you will begin to see Tree of Life signs again. The signs will lead you down a road which will then be devoid of these signs, but you will eventually see the tree in the distance on the right (it is large and wide, not to be mistaken for other smaller trees along the way). You turn onto a dirt path at Gas Well #371. You can drive up to just outside of the tree, but make sure you stay on the vehicle-worn path, as turning off of it is likely to get your car stuck in the softer sand.”

Source

READ MORE»

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Faisal Ansari

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Harold Laudeus – Flickr

Both its age and its location definitely make this tree a survivor, which is considered to be a remarkable natural wonder of the world witnessed by most who visit Bahrain.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Amer Olba™ – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Faisal Ansari

It stands alone, on top of a 25-foot-high sandy hill, at the highest point in Bahrain, miles away from another natural tree and with no apparent source of water. With 32 feet in height, it has continued growing-despite the extreme temperatures, lack of fresh water, and nutrients.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Harold the Heretic – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Shady_Myskus – Flickr

It has come to be known as the Tree of life due to the very fact that the tree stands amidst a hot and dry desert with no known water source feeding, which truly represents the magic of life and the power of nature.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Harold Laudeus – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: cannopia – Flickr

Serving to increase the lure of the place, the tree’s source of water is a mystery, because it stands in a place completely free of water. Plant scientist may say that its roots go very deep and wide to get water from the reserves of sweet springs kilometers away. The local inhabitants believe with heart and soul that the tree’s longevity is granted by Enki, the mythical God of water, and that it marks the location of the Garden of Eden.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Alex Europa – Flickr

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: stephenmichaelgray – Flickr

Surrounded by endless oilfields, from far away it looks like a green spot in the desert. The tree has several low hanging branches that spread out in all directions.

Tree of Life – Bahrain | Photo by: Glenn Rose – Flickr

Tree of Life Road – Bahrain | Photo by: triggerpit.com

The Tree of Life in Bahrain is located 1.2 miles or 2 kilometers away from Jebel Dukhan.

How to Get there:

“To reach the tree, take the Zallaq Highway heading east, which becomes the Al-Muaskar Highway. You will eventually see a sign for the Tree of Life indicating a right turn. (Although the sign seems to point you to turn onto a dirt road which actually goes nowhere, do not do so, instead wait until the next intersection which is several metres ahead). There are no signs as you travel down this road, but pay attention to a scrap metal yard on your right. Before you reach a hill which warns you of a steep 10% incline, take a right. As you continue straight down this road (including roundabouts), you will begin to see Tree of Life signs again. The signs will lead you down a road which will then be devoid of these signs, but you will eventually see the tree in the distance on the right (it is large and wide, not to be mistaken for other smaller trees along the way). You turn onto a dirt path at Gas Well #371. You can drive up to just outside of the tree, but make sure you stay on the vehicle-worn path, as turning off of it is likely to get your car stuck in the softer sand.”

Source