These electric blue shapes in the brown desert are potash evaporation ponds managed by Intrepid Potash, Inc., the United States’ largest producer of potassium chloride, and are located along the Colorado River, about 30 km west of Moab, Utah. These ponds measure 1.5 square kilometers, and are lined with rubber to keep the salts in. Unlike other salt evaporation ponds that get a naturally reddish tinge due to the presence of certain algae, the bright blue color of these potash evaporation ponds come from an artificially added dye that aids the absorption of sunlight and evaporation. Once the potassium and salts are left behind, they are gathered and sent off for processing.

Most of the world reserves of potassium came from ancient oceans that once covered where is now land. After the water evaporated, the potassium salts crystallized into large beds of potash deposits. Over time, upheaval in the earth's crust buried these deposits under thousands of feet of earth and they become potash ore. The Paradox Basin, where the mines at Moab are located, is estimated to contain 2 billion tons of potash. These formed about 300 million years ago and today lies about 1,200 meters below the surface.

To extract potash from the ground, workers drill wells into the mine and pump hot water down to dissolve the potassium. The resulting brine is pumped out of the wells to the surface and fed to the evaporation ponds. The sun evaporates the water, leaving behind crystals of potassium and other salt. This evaporation process typically takes about 300 days.

Intrepid Potash, Inc. produces between 700 and 1,000 tons of potash per day from this mine. The mine has been open since 1965, and Intrepid Potash expects to get at least 125 more years of production out of it before the potash ore runs out.

Source

READ MORE»

Most of the world reserves of potassium came from ancient oceans that once covered where is now land. After the water evaporated, the potassium salts crystallized into large beds of potash deposits. Over time, upheaval in the earth's crust buried these deposits under thousands of feet of earth and they become potash ore. The Paradox Basin, where the mines at Moab are located, is estimated to contain 2 billion tons of potash. These formed about 300 million years ago and today lies about 1,200 meters below the surface.

To extract potash from the ground, workers drill wells into the mine and pump hot water down to dissolve the potassium. The resulting brine is pumped out of the wells to the surface and fed to the evaporation ponds. The sun evaporates the water, leaving behind crystals of potassium and other salt. This evaporation process typically takes about 300 days.

Intrepid Potash, Inc. produces between 700 and 1,000 tons of potash per day from this mine. The mine has been open since 1965, and Intrepid Potash expects to get at least 125 more years of production out of it before the potash ore runs out.

Source

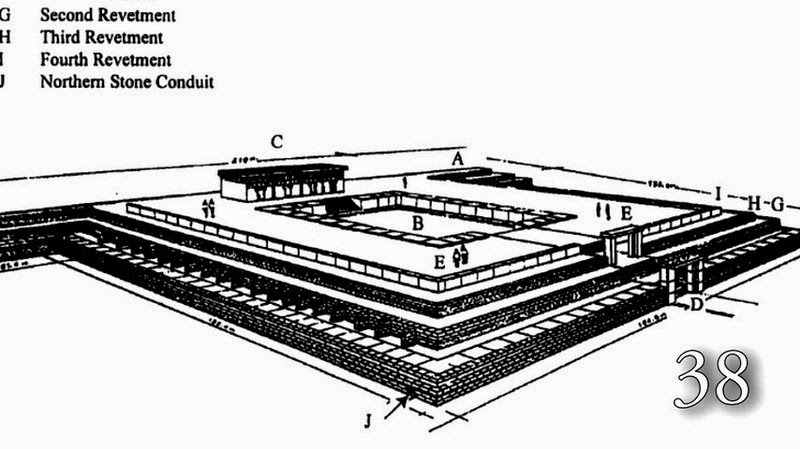

Satellite picture of Puma punku

Satellite picture of Puma punku