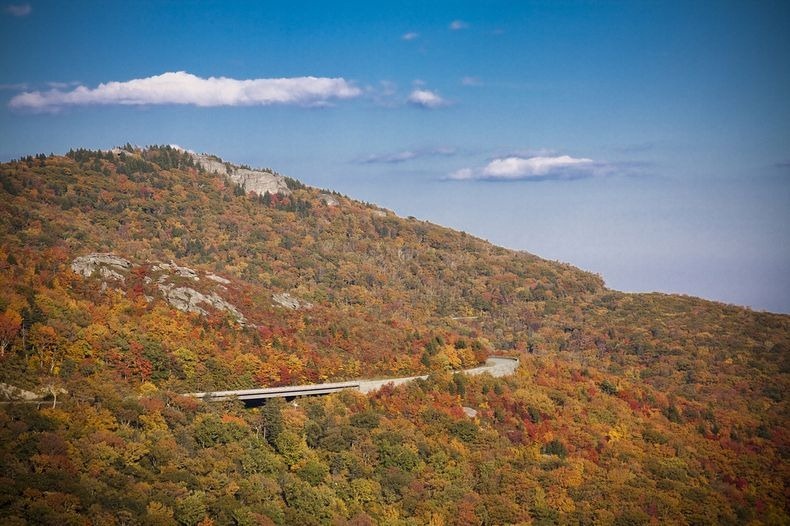

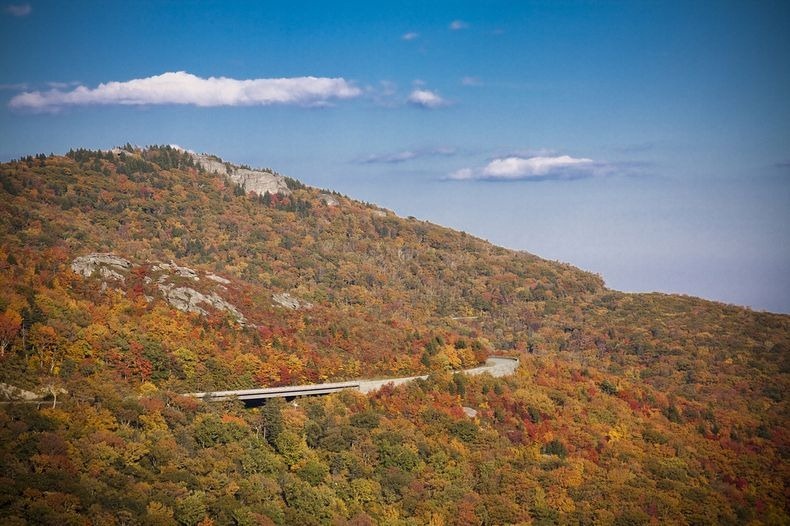

Linn Cove Viaduct is a 379 meter concrete segmental bridge which snakes around the slopes of Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina. Completed in 1987, at a cost of $10 million, it was the last section of the Blue Ridge Parkway to be finished, and considered to be one of the most challenging bridge construction.

The viaduct was built to minimize the damage that a traditional cut-and-fill road would have caused to Grandfather Mountain. Supported by seven massive pillars, the viaduct almost floats in the air without disturbing the land below. To eliminate damage to the environment, no access roads were built for transporting heavy equipment on the ground. The bridge's segments were precast at an indoor facility and transported to the bridge site, where each section was lowered into place by a custom crane placed on either edge of the existing structure. The only construction that occurred at ground level was the drilling of foundations for the seven permanent piers on which the Viaduct rests. Exposed rock was covered to prevent staining from concrete, epoxy, or grout. The only trees cut were those directly beneath the superstructure.

When engineers began constructing the Blue Ridge Parkway in 1935, they knew that building the Parkway that fit the terrain, particularly the Black Rock area of Grandfather Mountain, would be tricky. The whole area consisted of one large mass of boulders, cracked and loose, so conventional road-building practices would not have worked.

A key factor in this controversy was environmental concern. Engineers were faced with a serious question: How to build a road at an elevation of 4,100 feet without damaging one of the world’s oldest mountains? Studies and engineering schemes were done through the early 1970s in search of a plan for routing the Parkway through that area. Finally, the National Park Service landscape architects and Federal Highway Administration engineers agreed the road should be elevated or bridged, where possible, to eliminate massive cuts and fills.

The Linn Cove Viaduct is only the second bridge in history to be built from the end of a span, called a cantilever, which is anchored only at one end. In this case, the cantilever was the road itself. To protect the fragile terrain, all construction was done from the top down and no machinery was allowed more than 50 feet from the base of the piers.

Segments were trucked from a nearby storage area over the completed portion of the bridge to the end of the cantilever. There a stiff-leg crane lifted the segment, swung it out and lowered it to within six inches of the cantilever end. Epoxy was then applied to the joint face and the segment was moved to the cantilever end where the temporary thread bars were installed and stressed.

The contractors developed a special heating system to heat joints for the work to continue through the winter. The concrete used in making the Viaduct was tinted with an iron oxide pigment developed specifically for this project so that the color of the finished bridge would match the color of the one-billion-year-old boulders and cliffs that surround it.

The bridge was completed in November 1987 at a final cost of $10 million. Since then, bridge has received eleven design awards.

Source

READ MORE»

The viaduct was built to minimize the damage that a traditional cut-and-fill road would have caused to Grandfather Mountain. Supported by seven massive pillars, the viaduct almost floats in the air without disturbing the land below. To eliminate damage to the environment, no access roads were built for transporting heavy equipment on the ground. The bridge's segments were precast at an indoor facility and transported to the bridge site, where each section was lowered into place by a custom crane placed on either edge of the existing structure. The only construction that occurred at ground level was the drilling of foundations for the seven permanent piers on which the Viaduct rests. Exposed rock was covered to prevent staining from concrete, epoxy, or grout. The only trees cut were those directly beneath the superstructure.

When engineers began constructing the Blue Ridge Parkway in 1935, they knew that building the Parkway that fit the terrain, particularly the Black Rock area of Grandfather Mountain, would be tricky. The whole area consisted of one large mass of boulders, cracked and loose, so conventional road-building practices would not have worked.

A key factor in this controversy was environmental concern. Engineers were faced with a serious question: How to build a road at an elevation of 4,100 feet without damaging one of the world’s oldest mountains? Studies and engineering schemes were done through the early 1970s in search of a plan for routing the Parkway through that area. Finally, the National Park Service landscape architects and Federal Highway Administration engineers agreed the road should be elevated or bridged, where possible, to eliminate massive cuts and fills.

The Linn Cove Viaduct is only the second bridge in history to be built from the end of a span, called a cantilever, which is anchored only at one end. In this case, the cantilever was the road itself. To protect the fragile terrain, all construction was done from the top down and no machinery was allowed more than 50 feet from the base of the piers.

Segments were trucked from a nearby storage area over the completed portion of the bridge to the end of the cantilever. There a stiff-leg crane lifted the segment, swung it out and lowered it to within six inches of the cantilever end. Epoxy was then applied to the joint face and the segment was moved to the cantilever end where the temporary thread bars were installed and stressed.

The contractors developed a special heating system to heat joints for the work to continue through the winter. The concrete used in making the Viaduct was tinted with an iron oxide pigment developed specifically for this project so that the color of the finished bridge would match the color of the one-billion-year-old boulders and cliffs that surround it.

The bridge was completed in November 1987 at a final cost of $10 million. Since then, bridge has received eleven design awards.

Source